3 memorable Jason Dives

Volcanoes, vents, and creatures of the deep through the lens of ROV Jason

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

The Jason Team knows regions of the ocean floor like other people might know paths in their favorite mountain ranges. They’ve spent hundreds of hours in the remotely operated vehicle’s control van, where a bank of screens displays the deep sea from all angles. They’ve driven the vehicle over live volcanos, navigated to new hydrothermal vent fields, and encountered animals of all sizes. Jason dives have yielded no shortage of breathtaking underwater landscapes and adventure stories. Here are three of the most memorable.

1. Fire Underwater

The first time anyone captured video of an explosive volcanic eruption on the seafloor, WHOI Scientist Julie Huber and Jason Team members Tito Collasius and Akel Kevis-Sterling were watching it happen in real-time from the Jason control van.

It was 2009. The science team was using Jason to explore the West Mata Volcano near Samoa because there had been a recent eruption detected in the water column. They were looking for seafloor activity, but with no disturbance on the ocean surface and no discoloration of the water, they weren’t prepared for what they found when Jason dove.

“I was in the van when we made our first approach,” Tito said. “And we could see hydrogen explosions happening thousands of meters deep. They looked like balls of flame combusting underwater.”

The lava flow was so fresh they could see features forming on the seafloor they recognized from cooled basalt seen on other dives. “We could see the pillow lava forming,” said Kevis-Sterling. “It was still red and glowing.”

The science team began to improvise ways to collect the fresh lava, recalls Huber. Dating cooled lava is notoriously difficult, and having a sample with a known origin date would be invaluable. “We tried a ladle, a coffee can, and finally settled on spinning one of Jason’s T-handles in the flow.”

The same year, on another expedition, Jason’s cameras captured an erupting undersea volcano near the Island of Guam, NW Rota-1. Kevis-Sterling piloted the vehicle around the eruption.

“It was very active and gaseous, with lava shooting out,” he said. “It is shallow there and was hard to navigate the ROV and the ship. At one point Jason was working near the volcano and it started going bonkers and spewed ash all over it.”

2. Into the Woods

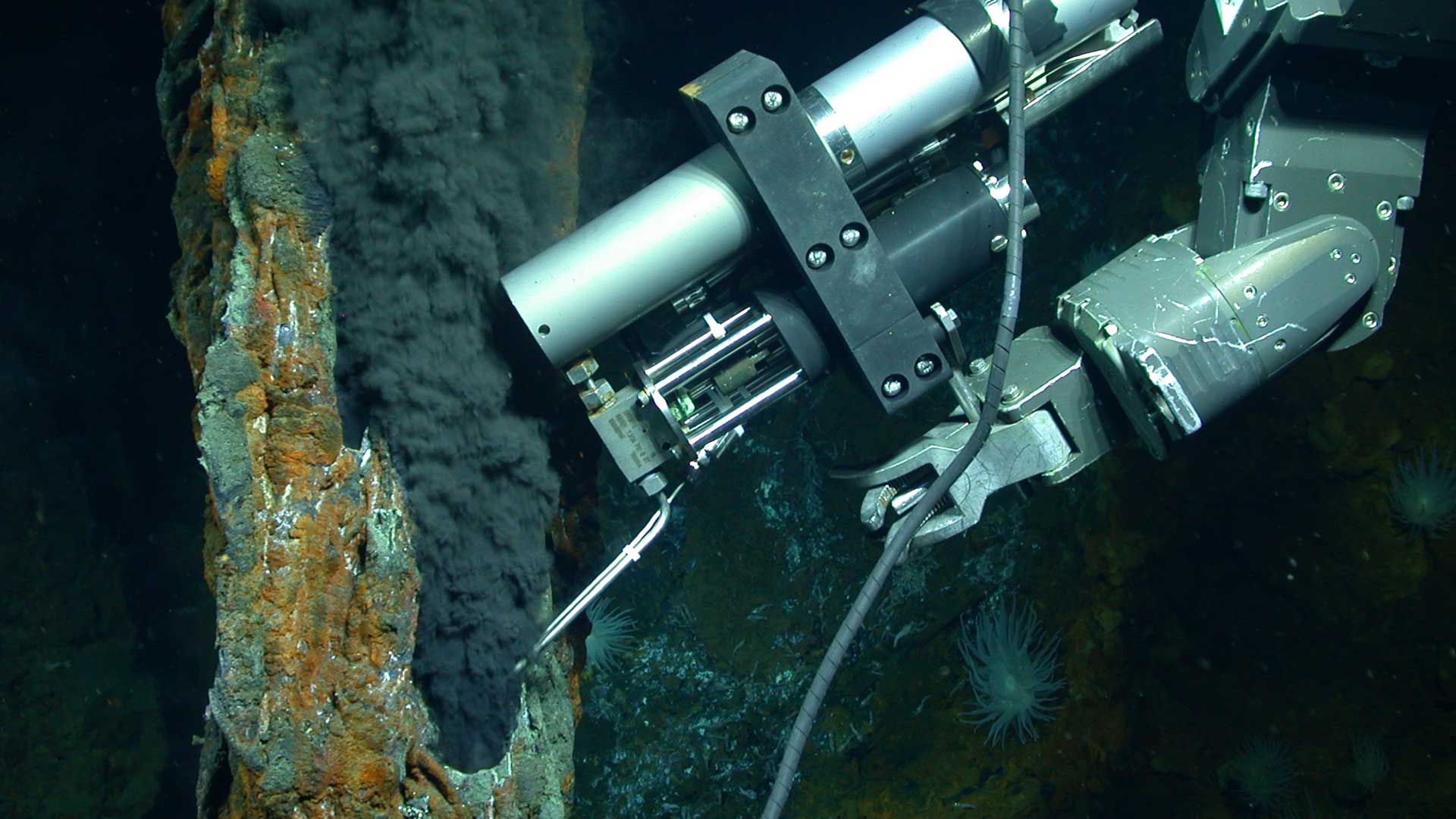

The discovery of hydrothermal vents was one of the most surprising of the past century, revealing volcanically powered, deep-sea plumbing systems that enable vibrant islands of life that exist without sunlight. In its current second-generation configuration, Jason has often been the first vehicle to explore these sites as they are being discovered, offering video and sampling capabilities as scientists pioneer this field of study.

Even after diving on hundreds of vent sites, it never gets old for members of the Jason Team.

One system that made an impression on Tito is at Lau Basin. Here, some of the vent’s sulfide towers reach 30 meters (100 feet) tall.

“It’s like being in a redwood forest,” he said. “You’re working at the base of one of these towers, and the visibility in the ocean is only about 20 meters (65 feet) at best, but all around you can see the bases of other towers. It’s like being in a forest only with hot smoke pouring out at the top.”

Huber was part of a WHOI team that first explored vents at the Mid-Cayman Rise in the Caribbean Sea in 2012. The rise is home to two very different vent fields, a deep one at a depth of 4950 meters (16,240 feet), and a shallow one at 3,000 meters (9,842 feet).

“And the deep site has these very tall skinny chimneys, with 398°C (750°F) fluid gushing out the top of them,” Huber said. “I remember there were five of them in a row—very well organized for random geology. They are really breathtaking.”

And then, just 30 kilometers (18 miles) away, the shallow site offers a very different manifestation of hydrothermal activity at a place called the Von Damm Vent Field.

“There’s no black smoke, all the fluids are clear, and at its summit there is a giant gaping hole so big you could fit Jason inside of it,” Huber said. “You wouldn’t do that of course, because the fluid coming out is about 220°C (430°F) and it is completely surrounded by shrimp. You approach it with the ROV and you feel like you’re just peering over the edge.”

3. Other Beings

When diving, Jason encounters sea life at every depth. On the descent, especially after dark, the surface ocean teems with gelatinous and soft-bodied animals: squid and jellyfish undulating in and out of view as the vehicle glides towards the bottom. The seafloor has a cast of characters: silvery rattail fish trailing the vehicle, spider crabs climbing into the basket, Dumbo octopuses making appearances. And of course, the worms, mollusks, and bacterial mats that thrive near vent systems.

Sometimes studying this sea life is the object of the dive—other times the life appears to be studying Jason.

“In New Zealand, just a few weeks ago, I saw a red squid maybe ten feet long,” said Jason Team member Hugh Popenoe. “It was on our ascent, so the van was empty and no one saw it but Akel [Kevis-Sterling] and me. It approached one of the lights and grabbed it, realized it wasn’t edible and took off. We didn’t get a second look at it. I had to go back into our video recordings to make sure I’d really seen it.”

“I’ve seen it all, glamorous Dumbo octopuses, angler fish with their light and big old teeth,” said Kevis Sterling. “We’ve had sharks aggressively try to intimidate Jason. They come right up to the vehicle and bump into it.”

But perhaps the most memorable sight of deep-sea life that many members of the Jason Team remember involves both seismic activity and creatures. If you’ve followed this team for any amount of time, you might have guessed it: Shrimpquake at Mid-Cayman rise.

Popenoe was in the Jason control van when it happened. “We were on the bottom at a vent that was covered in shrimp and then all the sudden all the shrimp pop up, and a few seconds later there was a sound like the thrusters of the ship being turned on. The geological wave from an earthquake hit the shrimp and then the water wave hit the ship.”

This story was adapted from blog posts on the National Deep Submergence Facility site from PROTATAX23, an ROV Jason expedition to Axial Seamount led by WHOI Chief Scientist Julie Huber in July 2023. PROTATAX23 is funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF OCE Award #1947776).